- Info@CooperativeMed.com

- 727-460-3101

Papers / Doctors Always In For Members Of Practice

SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 16, 2003 TAMPA, FLORIDA

THE TAMPA TRIBUNE And The Tampa Times

Doctors Always In For Members Of Practice

PALM HARBOR - Amid today's impersonal health care, when patients are "consumers" and doctors are "service providers," two physicians in Pinellas County aim to be different.

PALM HARBOR - Amid today's impersonal health care, when patients are "consumers" and doctors are "service providers," two physicians in Pinellas County aim to be different.

Michael O'Neal and Brent Agin, who opened their first practice last year, spend 30 minutes to an hour with each patient. Appointments start on time. They take phone calls at all hours, by cellular phone or pager. They make house calls.

The extra service is not free. Patients pay an annual retainer - $1,000 for individuals, $2,000 for families - to join what O'Neal and Agin call "a personalized membership medical practice." Although many family medicine doctors see 7,000 patients or more, O'Neal and Agin plan to limit their practice to 700.

"We thought it was time that young physicians come out of their residencies and challenge the system," said O'Neal, who completed a family medicine residency at the University of South Florida last year.

Also known as boutique or concierge medicine, a handful of similar practices have emerged in places such as Seattle and Palm Beach

The concept: By sharply limiting the number of patients in their practice, doctors escape the limitations of managed care and patients get better service. The catch: Patients pay annual fees to doctors in addition to having health insurance or Medicare to cover tests, procedures and hospital stays.

Critics argue that concierge medicine isn't fair because many patients can't afford to join. When doctors convert their practices, they may cut caseloads, dropping hundreds of patients.

Restoring Rockwell's America

Barry Berger, 51, of Palm Harbor doesn't care about the rhetoric. Berger, who is disabled, is happy to pay $2,000 a year for his family to receive care from O'Neal and Agin. Berger was injured severely in a fall and uses a morphine pump for pain. He estimates that Agin has made up to 30 house calls in the past six months.

Agin gave him a flu shot at home and checked his blood pressure and medications. Berger's mother, who lives with Berger and his wife, also is Agin's patient. She is 81 and requires care for a bad knee.

"People say this is elitist medicine for people with money. It's not that," said Berger, who once called Agin at 11 p.m. when he was having trouble breathing. "This goes back to medicine that we used to know. It reminds me of the picture by Norman Rockwell" in which a kindly doctor is about to give a shot to a little boy.

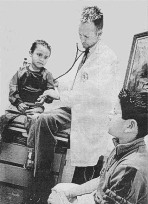

As Jake Rosenhaus, 4, is examined by Michael O’Neal, brother Taylor, 7, awaits his turn at the practice that offers it’s members specialized attention.

Social, Ethical Questions

Ronald Kaufman, a USF College of Medicine professor who teaches students about running a medical practice, compares boutique medicine to flying: Those who pay the most get better seats.

As for charging retainers to maintain income while restricting caseloads, Kaufman said, "As a social good, it bothers me." Doctors pledge an oath to heal patients, he says. However, health care policy in the United States has been to treat medicine as a commodity, making virtually every sector a for-profit business, Kaufman says. "If it's a commodity, then it's a free country," he said. "Who am I to say that [a boutique practice] is morally improper?"

Doctors are squeezed between the rising costs of malpractice insurance and lower payments from private insurers and Medicare, says Tad Fisher, executive vice president of the Florida Academy of Family Physicians. To cover overhead and maintain their level of income - about $144,000 for family medicine doctors - they must see more patients. Regulations, paperwork and billing hassles add to the stress. "The volume of patients is higher than it's ever been, and the amount of time spent with each patient is lower than it has ever been," Fisher said. "That's really the business of medicine," he said. "It has evolved to that, since the onset of managed care" that began in the 1980s.

Pioneering Practice

O'Neal and Agin say they are the first doctors in the country to start a concierge practice from scratch. They didn't want to have to drop patients later if they converted a traditional practice with thousands of patients from managed care contracts. They opened the Center for Family Health, Wellness and Prevention in August on Tampa Road near U.S. 19. They have enrolled about 175 patients.

Despite student loan debts of $200,000, O'Neal says the ability to spend time with patients is worth the risk of doing business his way. "The problem with managed care...is the high volume and the time to devote to each patient. I like to refer to it as diluted care," he said.

The two doctors accept insurance from companies such as Cigna and Humana, which cover services such as lab tests and hospitalization. But they don't have contracts with any HMOs, which assign people to a primary care doctor who sees large volumes of patients and controls access to specialists.

"In managed care, you're in and out. I didn't want to spend seven to eight minutes with my patients," Agin said. "That would really drive me crazy. That's not why I got into medicine."

Other area doctors have expressed interest in boutique practices but none has been as public as O'Neal and Agin, says Carolyn Caldwell, the Pinellas County Medical Society's executive director. "There may be some who are doing it, but they aren't advertising it as such," she said.

Humanizing Doctors

For Brett Rosenhaus, 38, an insurance executive in St. Petersburg, paying to be a patient was the only incentive to get him to a doctor. He enrolled his family, which includes two elementary school-age sons, in O'Neal and Agin's practice last year.

I really don't like doctors ... I'm a big baby. I'm afraid of needles and things like that," Rosenhaus said. "A big part of overcoming that fear is humanizing it. These guys have really humanized the practice," he said.

When Rosenhaus noticed a slight tenderness in a testicle, he got an appointment with O'Neal the same day. "I didn't have a chance to think about it and wimp out" of seeing a doctor, he said. The suspicious growth required consultations with urologists and tests. "I must have called 10 times to discuss it," Rosenhaus said.

He saw a University of Miami specialist, who said the growth could be removed immediately or Rosenhaus could wait three months to see whether it grew. Rosenhaus was going to wait. But when O'Neal and Agin strongly urged him to choose the surgery, he took their advice.

A 1-centimeter lump, removed two weeks ago, turned out to be testicular cancer. Because it was caught so early, chances are good that the cancer won't recur, Rosenhaus says.

He doesn't want to give up concierge health care. "Now that I have it, it would be very difficult to change back."